Watchmaking's Crisis – And Comeback

The closing of one U.S. watchmaking school and concurrent opening of a Rolex training center tell the story of a profession struggling to meet booming demand.

Good morning from Midway Chicago Airport, where I’m about to catch a flight to New York for the final large auctions of the year.

Yesterday, I bid by telephone in an auction for the first time. The auction’s live bidding platform was down, so a specialist called me as the lot I was interested in came up. Even though we were only bidding $200 increments for a watch that, honestly, isn’t rare, I got entirely caught up in the heat of a live back-and-forth. I’ve always been an online bidder, and while it’s easy to click that “Bid Now” button just one more time, it’s just as easy to close the window and go back to doomscrolling. It’s cold and devoid of excitement, no different than buying toilet paper from Amazon.

But when live bidding, even by phone, emotion and ego quickly take hold. No, I’m not gonna let some online bid from Connecticut — probably some private equity prick! — take this from me. Over what, another $200? Bidding!

All this to say: I bought a watch yesterday, and ended up paying a bit more than I meant to. If you’re bidding at the larger sales this week, stay sharp!

In this week’s issue: What I learned from three U.S. watchmakers about the state of watchmaking education; So you wanna buy a vintage Cartier Tank?; How the Hans Wilsdorf Foundation spends its money; Jacob the Jeweler; and a Watch of the Week you can bid on.

There aren’t enough watchmakers in the United States. Anywhere, really, but let’s focus on the U.S. Today, there are about 1,900 watch and clock repairers; just five years ago, there were 2,800.

“The number of watchmakers isn’t sufficient right now,” says Nick Manousos, Executive Director of the Horological Society of New York. He explained that the number of retiring watchmakers is much larger than new graduates entering the workforce.1

This basic fact is changing watchmaking education. There are only a handful of watchmaking schools in the U.S. HSNY counts nine. One of the more well-known schools is Lititz Watch Technicum (LWT) in Pennsylvania.

LWT is closing in spring of 2025.

Rolex founded LWT in 2001, and as it explains on its charitable website:

“Rolex entirely finances and equips the Lititz Watch Technicum, and underwrites the tuition fees at the school. Students buy their own watchmaking tools – a substantial financial investment at their age, but one that stays with them for a career.”

LWT offered a two-year curriculum, with students only paying for their own tools (about $6,500 for the school kit, though many students buy more tools).

While Rolex continues to support the two-year Watch Technology Institute at North Seattle College, it also recently opened the doors of its new Rolex Watchmaking Training Center in Dallas. The two schools represent alternative approaches to watchmaking education. Both are needed to address the shortage of watchmakers.

A couple of weeks ago, Hudson Mickey, a second-year watchmaking student at LWT visited Chicago. Since Hudson is part of LWT’s last graduating class of 15 students, we chatted about his experience. I also spoke with Manousos of HSNY (a trained watchmaker), and watchmaker Zach Smith of Hour Precision.

Take me to school

Traditionally, watchmaking school is a two-year program. For example, LWT offered a two-year SAWTA (Swiss American Watchmakers’ Training Alliance) curriculum. SAWTA was developed to standardize curriculum design, testing, and certification, primarily for Rolex-funded schools in the U.S.

“For the first 2-3 months of class, it’s heavy on information and laying a foundation,” Hudson said of his experience. “There’s very little hands-on work. But after that, the doors open.” Students start by working on movements provided by the school, but before long, they can bring in watches for “real-life repair” – anything outside of what’s assigned. For the past year, Hudson said he’s been servicing watches nearly all day, every day.

Watchmaking students learn two broad sets of skills:

Watch service

Micromechanics

Watch servicing includes the basic building and deconstruction of movements, regulation, and oiling – all the skills needed to diagnose and fix a problem when a watch comes in for after-sales service.

Micromechanics is the actual production of parts. Students learn to cut and shape metal – how to measure, lathe, cut, or mill components on a micro-scale.

But the shortage of watchmakers is changing how brands and the industry approach education.

“Some programs have been shortened to one year or 18 months,” Manousos said. “These are really watch technician programs,” focusing more on specific tasks for specific watches. They teach the more limited skillset required for competency in after-sales service. Typically, these are brand- or group-specific curricula; however, these shorter programs often aren’t adequate if a watchmaker wants to later switch brands or work independently.

The Rolex Watchmaking Training Center that opened in Dallas in 2023 offers an 18-month program, after which graduates will be Rolex certified after-sales service watchmakers.2 The main benefit of these programs is that they train more watchmakers, and more quickly.

These shortened programs often exclude micromechanics from the curriculum. Manousos said the average watchmaker today “rarely uses micromechanics,” likening it to calculus, a cold reminder that I certainly couldn’t find a derivative.

“Some students really enjoy micromechanics, but others don’t because they feel they’re never going to use it,” Manousos said.

Hudson is one of those students who enjoys micromechanics, saying he values developing the skills required to manufacture parts or tools he’ll need to be a truly independent watchmaker.

“These [shorter] programs get more people servicing watches in a shorter amount of time, but the trade-off is that they may not have the foundation a fully certified watchmaker might have,” Manousos added.

The service shortage

Rolex founded LWT in 2001 to address the shortage of watchmakers. Between 1973 and 2000, watchmakers in the U.S. decreased from 32,000 to 6,500 (remember, today there are about 2,000). But traditional watchmaking experienced a rebirth in the 1990s. With that came a need for more service and repair.

Fueled by the pandemic, watches have experienced similar growth over the past few years, only increasing the need for skilled watchmakers.

This shortage means that overwhelmed brands and service centers increasingly emphasize fast and efficient service. They’d rather have their (certified) watchmakers quickly swap out parts than fix components or manufacture new ones, which takes longer. While this can make service more efficient, which can ultimately be good for consumers who get their watches back faster, it can come at a cost.

“I felt like a robot at Swatch Group,” says watchmaker Zach Smith. After graduating from the Nicholas G. Hayek Watchmaking School in Miami and working as a watchmaker at Swatch, Smith founded his manufacturer, Hour Precision. Larger brands are addressing the influx of service requests by making becoming more like Adam Smith’s pin factory, dividing labor to drive efficiency and productivity. But this also provides an opportunity for small operators like Smith to do things differently.

“There are so many jobs we can create,” Smith said. He first focused his business on servicing, but soon pivoted to assembly and manufacturing.

“Getting parts from these brands for service was impossible,” Smith said. “It made me realize I can’t create a business by relying on them.”

To create something truly independent and sustainable, he decided he’d need to build his own manufacturing and assembly capabilities. He became an expert in CNC and micromechanics, and now he’s making tiny parts not just for watches but for the types of big tech companies that hold him to ironclad NDAs.

Smith says he’s thinking more holistically about watchmaking and sees no limit to the amount of jobs he can create – not only movement manufacturing and assembly, but cases, bracelets, dials, and so on.

Meanwhile, he expressed disappointment at the current direction of watchmaking education in the United States.

“A lot of these schools are just teaching students to change parts,” Smith said. “You need experience behind the bench. You need these basic skills. Micromechanics isn’t being taught in schools, but someone eventually has to bear that weight.”

As one of the few shops building real manufacturing and micromechanics capabilities in the U.S., Smith says that burden – and cost – might fall to folks like him. If independent businesses like his can’t shoulder the burden, consumers might bear it in the form of higher service costs. (If you’ve had a watch serviced recently, you know this is already kind of true.)

Striking a balance

Still, the watchmakers I spoke to are more optimistic than ever about the state of watchmaking in the United States, especially independents.

“Watchmaking in the U.S. is in a really good place,” Manousos said. “I’m happy to see the investments being made in American watchmaking – not marketing, but actual watches being made in America.”

“It’s like the Wild West right now,” Smith added, pointing to the number of rising small and independent watchmakers in the U.S.

For his part, Manousos says the various education strategies are reaching a sort of equilibrium.

While some brands have put more support behind shorter programs focused on servicing their own watch movements, HSNY continues to emphasize two-year programs capped by students making their own school watch.

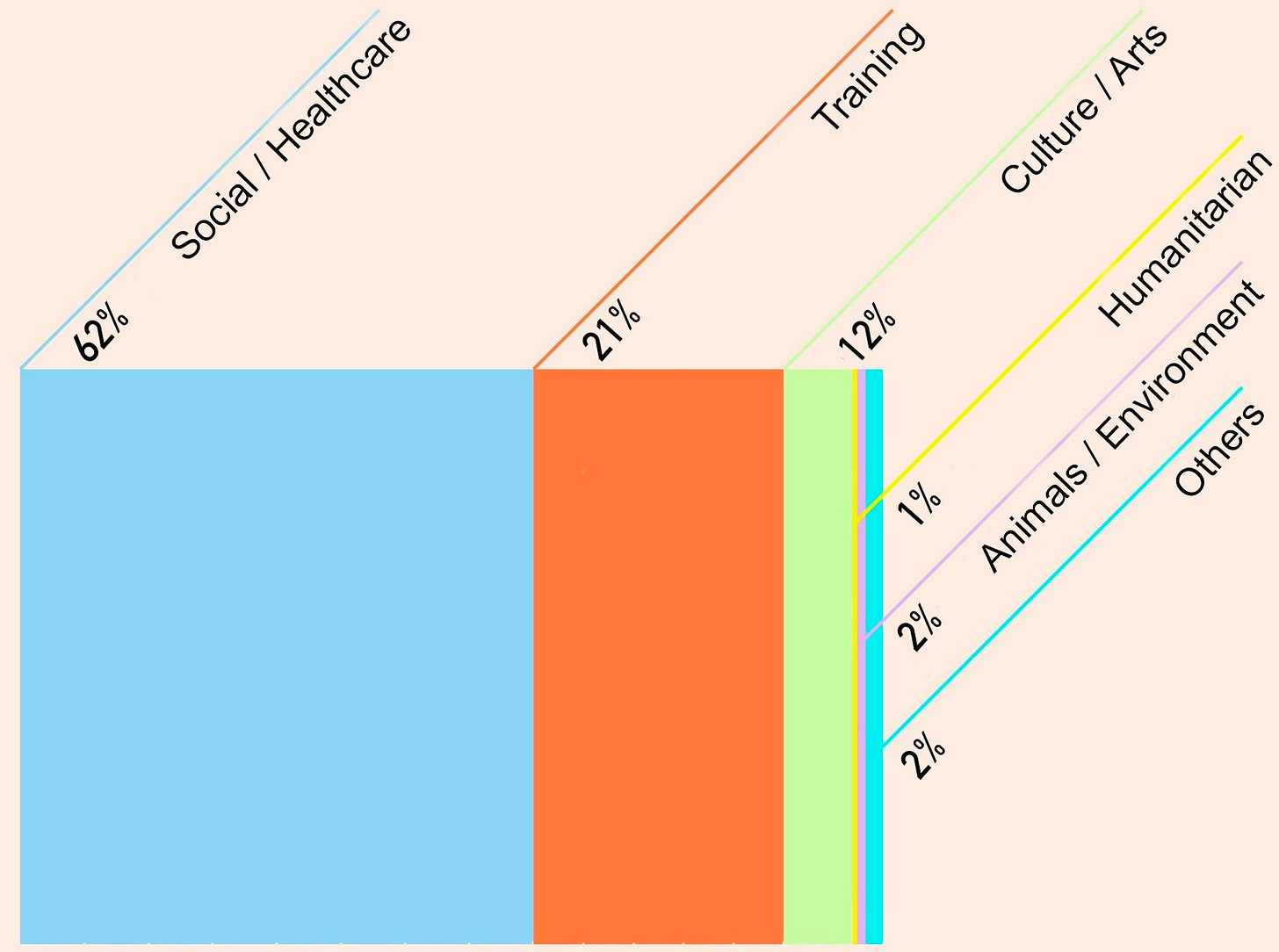

And remember, HSNY is a non-profit, mostly supported by brands, so money is already being spread around. It’s a lot of money, too: this year, the Hans Wilsdorf Foundation, the non-profit that owns Rolex, donated 21 percent of its funds to “Training” according to its recent report (more below) – its second-highest donation category. HSNY lists many large brands as sponsors.

“We recently introduced an award for the student who makes the best school watch in the U.S.,” Manousos said, adding that he was pleased by the response as it has encouraged some schools to restart the long-standing school watch tradition.

“More programs only makes becoming a watchmaker more accessible to those who want to do it,” Hudson added. While students might not pick up traditional micromechanics and manufacturing skills in school – especially important for vintage restoration – it gets more watchmakers into the system who might have an interest and independently seek out that knowledge later in their careers.

My View: A watchmaker is not a technician

LWT’s closing comes just six years after Oklahoma State University’s SAWTA-certified watchmaking school also shut down. It’s easy to feel incredulous that these two-year programs teaching traditional techniques are shutting down just as Rolex is opening a dedicated training center in Dallas.

But Rolex also founded LWT, and it’s supported so much of the broader watchmaking education effort in the U.S. It’s good business that also happens to feel magnanimous: the shortage of watchmakers is probably felt most acutely by (1) customers waiting for months on end for their watch to come back from “the spa,” and (2) Rolex, the largest watch brand on the planet.

Training centers like Rolex’s new facility in Dallas place an emphasis on training more students. Given the shortage, that’s probably what the industry needs most now. Rolex alone sells more than a million watches a year and shows no signs of stopping. Many of those watchmakers will work in after-sales service. It’s just not realistic to teach all of these kids micromechanics if many of them will be swapping out mainsprings. For those who don’t, additional skills can be taught or picked up further along in their career. But that learning can be expensive.

A healthy industry also needs entrepreneurs like Zach Smith or Josh Shapiro who are building an alternative apparatus, almost completely in parallel to these large Swiss brands. There must be opportunities for creative, independent watchmakers who want to do more. Importantly, large brands should also find ways to support this independence, recognizing that it’s vital to the long-term viability of watchmaking. Think of initiatives like the Louis Vuitton Watch Prize or the F.P. Journe Young Talent Competition.

Watchmakers are the lifeblood of this industry. Training them is expensive, but without watchmakers, there is no watch industry.

Note: Rolex did not respond to a request for comment.

Oil rigged

YouTuber Nico Leonard recently mentioned the serious allegations against the leader of a certain watch brand. Nico might be Five Time Zones away from me, but he’s right that this brand has previously received outsized attention from the media, especially relative to its actual watchmaking. And now, crickets. Jacob Arabov, the man behind Jacob & Co., is a named defendant in one of the many lawsuits against Diddy. The allegations are well beyond the scope of a mostly not-serious newsletter, but it’s worth mentioning, given this guy’s name is literally on watches.

Support this newsletter

If you enjoy this kind of in-depth, original reporting and analysis, please consider pledging your support. This unbiased, collector-driven coverage of the watch industry will only be possible with the support of paid subscribers like you.

I’ll be officially launching paid subscriptions in about a week. If you remain on the free list, you’ll receive the occasional newsletter. Paid members ($99/year or $10/month) will receive 2 newsletters/week. Founding Members ($290/year) will also receive a custom valet tray from Chicago-based Veblenist. An official “relaunch” with more info on subscriptions is to come, but you can pledge your support now:

What Does Rolex Spend Its Money On?

The Hans Wilsdorf Foundation, the Swiss non-profit that owns Rolex, released new donation data for its year ending in June 2024. Relevant to this week’s article, it gave 21 percent of donation funds to “Training” (down from 29% last year).

This is the best reporting I’ve seen on Rolex’s charitable efforts: Rolex earns billions every year. Where does the money go? (NZZ)

“Every year, we have around 300 million Swiss francs available for charitable purposes. When major projects come up, it can sometimes be significantly more,” the Wilsdorf Foundation’s Secretary General told the Swiss paper NZZ. Much of these funds are directed to projects in Geneva: architecture and public works, saving a football team, majority ownership of Le Temps newspaper, and more. Rolex-dedicated blog Coronet has more on the Foundation here.

THE WATCHLIST

So You Wanna Buy A Vintage Cartier Tank Louis?

Hunting for a Cartier Tank Louis feels kind of like looking for a public bathroom. You assume they’re everywhere, but when you really want one, it’s impossible to find.

Even though Cartier’s been making the Cartier Tank for 100+ years, most examples look mostly the same. Still, if you’re at all interested in the Tank, it’s important to have a broad understanding of its many quirks.

So I thought I’d do a true Watchlist, giving a rapid-fire rundown of eight Cartier Tank Louis examples coming up for auction in the next couple of weeks. This should probably be a precursor to a longer article. But until then, here’s the Spark Notes.

First, some background

Cartier introduced the Tank Louis in the early 1920s. Until 1960, Cartier only produced about 15,000 wristwatches. Production picked up at Cartier Paris and London in the ‘60s, but only a bit. A 1960s Cartier Tank is still an incredibly special, handmade thing.

After the reunification of the Cartier New York, Paris, and London branches in 1972, production ramped up. As I covered in my Collector’s Guide to 1970s Cartier, the brand partnered with Ebel to move its watch production to La Chaux-de-Founds, Switzerland.

The gold cases and white enamel dials of these 1970s watches are still well made, but they feel more like mass-produced luxury compared to those earlier Cartier watches. These 1970s watches also downgraded to ETA movements from higher quality movements, often from Jaeger-LeCoultre.

With the historical context set, here’s a selection of Cartier Tank Louis examples coming to auction, along with one to watch out for.

1960s: Tank Louis

1966 Small Cartier Tank Louis. Historically, Cartier produced the Tank Louis in two sizes: 20x28mm and 23x30mm. This is an example of the smaller size, with its serial dating to Cartier Paris, 1966. The caseback has an eagle beak hallmark and “EJ,” short for Edmund Jaeger, Cartier’s watchmaker during this era. Auction on December 10.

1968 Large Cartier Tank Louis. Similar to the previous Tank L.C., but in the large size. It has the same eagle beak and “EJ” hallmarks on the caseback, indicative of ‘60s Cartier Paris. Like the previous Tank, it also has its original dial. Auction on December 9.

1970s: Cartier Tank ref. 78086 & Tank Automatique ‘XL’

Tank Louis examples from the 1970s are easier to find. It’s estimated Cartier produced about 15,000 examples of the ref. 78086 throughout the ‘70s and ‘80s.

There are at least a few at auction this month: Aguttes (Dec. 9), Sotheby’s (ending Dec. 13), and Finarte (Dec. 16). If condition is equal – no cracks in the dial, a relatively strong case, etc., I tend to prefer earlier examples with the longer cabochon crowns like the example in the first photo above.

Alongside the standard large Tank Louis, Cartier also produced the Automatique XL in much lower numbers throughout the ‘70s. There’s one at Tajan on December 10.

1990s: Cartier Tank CPCP

In the 1990s, Cartier introduced the CPCP collection, a line of limited-edition watches that celebrated its heritage by reinterpreting iconic designs with high-quality craftsmanship and mechanical movements from makers like F. Piguet, Piaget and Jaeger-LeCoultre.

Among those is the Tank ref. 1601. It updates the classic Tank with a beautiful guilloche dial and F. Piguet cal. 21. One of my favorite takes on the Tank, this example is at Finarte in Milan.

Buyer Beware: 1950s Tank L.C.

Finally, here’s a small Tank Louis to watch out for. It’s a pre-1970s Tank Louis: It has an eagle hallmark, European Watch Co. movement, and an octagonal crown often seen on this era of Tanks. The serial number dates the case to 1954.

Unfortunately, it also has a service dial, here easily recognized by the “Swiss Made” at 6 o’clock. Note that it’s much more similar to the 1970s dials above than those from the ‘60s. This takes away much of its true vintage charm.

This Tank Louis was at Wright Auction yesterday, but with a starting bid of $10,000, it (rightly) failed to get a bid.

Finally, I’m looking to bring on newsletter sponsors for Q1 of 2025. Advertisers will be for the weekly free newsletter (and not the second letter that will go out exclusively to paid subscribers). As a reminder, newsletter sponsorship will not be open to watch brands. I’m open to any other potential partners that might make sense for both of us, so reach out if you’d like to have a discussion.

Email tony@unpolishedwatches.com and I can provide our media kit.

See you next week,

Tony

Watch Of The Week: A Charity Auction for Everyone

As part of its New York sale next week, Christie’s is hosting a charity auction supporting the Brian LaViolette Foundation. Brian tragically died in a swimming accident when he was 15, and his parents started a scholarship foundation to honor his memory. All proceeds from the hammer price of each lot will go to the Foundation. Dealer Eric Wind has helped to curate the sale, and it features a nice variety of vintage and modern watches across price points.

I’ll be in New York for auction previews this Thursday-Friday, but was already able to see the lot donated by Cornell Watch Company. They’ve created a unique version of their first model, the 1870 (here’s my review on Hodinkee), in collaboration with Roland Murphy, featuring a double-sunk Grand Feu enamel dial. Even better, it’s offered with the original Cornell pocket watch from the 1870s that inspired the dial. (Est. $5,000–8,000). To check out the full sale, head to Christie’s.

“Anecdotally, about 100 watchmakers are retiring each year,” Manousos estimated. Right now, the handful of watchmaking schools in the U.S. graduate about 50 students per year.

According to the Training Center’s website, the final exam is administered in Geneva, and Rolex covers all expenses for the trip.

Great read. Watchmaking schools seem to have such a peculiar model. One question I’m left with after reading…is there a prevailing theory on why these schools are closing? Is it a lack of applicants? A lack of sponsors to sustain the cost of the schools? Does America need more schools, or just more young people with a desire to become a watchmaker?

Tony,

Great newsletter, as always.

I was looking at watch articles this week and came across this article from Gear Patrol about a new Casio Sauna Watch.

https://www.gearpatrol.com/watches/casio-sauna-watch/

I was surprised when the article mentioned that G-Shocks cannot handle a steam room. I thought those things could withstand almost anything? So, is this Casio watch the only watch that can be worn in a sauna-like environment? Wouldn't dive watches be able to handle something like that?

I never go in saunas, but I like weird watches, which almost makes me want to buy one.

-Bob