The Problem with Provenance

Collecting the Jaeger-LeCoultre Reverso; on gatekeeping; and what are you doing with your watch?

Happy Friday. The other day, I posted this screenshot of an Instagram comment from noted Cartier enthusiast Tyler, the Creator:1

Based on the overwhelming response, a lot of you are also FOR GATEKEEPING.

Watches are already probably one of the more gate-kept hobbies around. There’s a constant balance to strike between welcoming people in but making them earn it, whatever that means. E.g., when Dave Portnoy makes a sh**ty watch, we nerds come for him, spring bar tools in hand. That’s good gatekeeping! There are also all kinds of examples of bad gatekeeping. The past few days had me thinking: Do watches need more or less gatekeeping?

In this week’s letter: Gamal Abdul Nasser and his Rolex Day-Date, GQ, Heuer, the Jaeger-LeCoultre Reverso, Rolex Milgauss, Steve McQueen, and more.

Okay, on with this week’s GATEKEEPING.

The Problem with Provenance

One of the weird sensations about an auction is that you can go to a preview and put on a seemingly normal watch that, the next day, is worth a million bucks.

Such was the case with the “president’s President.” Last week, Sotheby’s sold former Egyptian president Gamal Abdul Nasser’s Rolex Day-Date ref. 1803 for $840,000, about as far from its $30-60,000 estimate as peace is in the Middle East. It was given to Nasser by another Egyptian president, Anwar El Sadat.

When I strapped the Day-Date on my wrist before the sale, it was, nominally, a $60k proposition. A day later, almost a million dollars – which, btw (I think) makes it the second most expensive publicly-sold Day-Date ever?? (After the $1.3m Rainbow Khanjar).

The story of Nasser’s Day-Date clearly resonated with the market – the final price was perhaps (unsubstantiated speculation!) the result of a bidding war between Rolex itself and big-time Middle East $$ (rumor is the former won – if you come at the King…)

The thing is, the story of the “president’s President” didn’t resonate with me. I get that I’m not the audience for this particular story. Nasser and Sadat are far-away figures from history books, about as abstract as euclidean geometry.

But it’s not just Nasser and his Day-Date. I’m always struck by how little these stories of specific provenance move me.

Across the auctions last week, stories and provenance were the themes, as they often are. “We’re really focusing on watches that have stories, narrative, and presenting them in an auction setting that’s fun,” Geoff Hess, Sotheby's global head of watches, told me for my auction recap in GQ.

Sotheby’s did a great job telling the story of Nasser’s Day-Date. The provenance was legit, complete with a heartfelt letter from Nasser’s grandson who inherited the watch before consigning. They also found photos of Nasser wearing the watch during notable moments of his life and political career, properly placing the Day-Date in its historical context. The literal manifestation of all those “men who guide the destinies of the world wear Rolex” ads.

As a brand or an auction house, I even understand focus. These stories can turn an ordinary object into a historical artifact worthy of a million-dollar bid and a spot in a museum.

Besides Nasser’s Rolex, there was also Steve McQueen and his Monaco – or, one of six McQueen Monacos – which sold for $1.4 million, along with any number of the vintage Heuers at Sotheby’s with specific ties to racing and motorsports.

In theory, those racing stories in particular should resonate with me. I’m a kid who grew up in Indianapolis, going to the Indy 500 some years and playing that odd golf course in the infield even more often. But they still left me wanting.

Here’s the thing though: I do love Heuer. Vintage Heuer feels like the working man’s Rolex.2 Specifically the Carrera – it’s got a cleaner design than the Daytona and a better case than the Speedmaster. Those old photos of Jo Siffert or Mario Andretti or even Mick Jagger wearing a Carrera? **Chef’s Kiss**

But those photos make me appreciate the durability of the watch itself. Not just “durability” in the sense of it being a well-made thing, though quality is part of it. I also mean its durability against time and trends. I mean the Carrera’s ability to adapt from the wrist of Andretti or Siffert to that of a kid who knows more about the golf course inside the Speedway than he ever will about hitting the apex going around turn 3.

Respect the Milgauss

There was also this gorgeous, original Rolex Milgauss ref. 6541 at auction last week. It’s got wear and tear but felt honest and original in all the right ways, passing from the original owner through a dealer who consigned it to Christie’s. It came with this story about how the original owner was a CIA operator who participated in the Bay of Pigs and was eventually imprisoned in Cuba for almost two years.

But all that was before he even owned the Milgauss!

I’m not saying it’s not a cool story. It is. I’m just not sure how relevant it is to this Milgauss.

The Milgauss passed at auction, meaning it didn’t sell. I’m not here to say whether it should’ve passed its reserve price, but it didn’t get a bid past $130k, a good bit under its $150-250,000 estimate. It could be a simple case of Milgauss fatigue after Rolex paid $2.5 million for one last year.

But the Milgauss is a great watch! The honeycomb dial. The lightning hands. Only a couple hundred made! This one had a slightly brown dial, and while there was some aging on the dial and hands, it felt honest for a watch that’s turning the corner on 70.

All I’m saying is that, for most watches, focusing on the durability of the object itself is as compelling as any story of specific provenance.

Hell, look at Tom Brady’s watches. While his ownership drove a premium for his modern IWCs and GMT-Master (a $60k Batman!?), the “GOAT” provenance didn’t mean much for the bigger ticket items like his 3970 or John Player Special. The watches – that’s what actually lasts.

It’s part of the genius of that Patek tagline: You don’t own a Patek Philippe, you merely look after it for the next generation.

It’s all about you. Not Steve McQueen or Tom Brady or some CIA operator. You.

All of these vintage watches carry a bit of history, whether or not they have a specific narrative. This durability of quality, design, and against trends – and what you do with it – that’s the most interesting story.

For more auction coverage, here’s my recap for GQ.

THE WATCHLIST

A Killer Collection of Vintage Reversos

A few watches are completely undervalued based on their historical importance and rarity. First among these is the Jaeger-LeCoultre Reverso. The Reverso was introduced in 1931 and produced through the early 1950s before JLC stopped making it until 1972. That’s when the Corvo family insisted the brand bring back the Reverso in a small test run for the Italian market, a story I wrote about earlier this year.

On Monday, Italian auction house Finarte has a nice run of vintage Reversos in its Watches sale. It’s a nice study of the first couple generations of the Reverso produced throughout the 1930s and ‘40s.

I reached out to Finarte and they sent over a few more photos of the watches.

Related to the discussion above: I also asked Finarte if these watches had any special provenance or story with these watches. After all, it’s not every day you see a handful of true vintage Reversos in one sale. Here’s what Alessio Coccioli, head of Finarte’s watches department, said:

“Honestly, the Reversos don’t have any particular provenance or history behind them, they come from three different owners, and I simply had the opportunity to create a theme section of the catalogue.”

This is what I mean! A good watch doesn’t need some story or provenance to sell. It’s just a good watch.

The original Reverso measures 38x23mm, which makes it a touch bigger than a traditional Cartier Tank. It’s the perfect size for the Reverso that the modern brand – finally – brought back with the new Monaco Tribute released earlier this year.3 Meanwhile, those ladies’ Reversos are tiiiiny.

Here are the five Reversos from Finarte, also seen in the photo above:

Lot 84, 1st-gen vintage Reverso

Lot 85, 2nd-gen two-tone Reverso

Lot 86, 2nd-gen Reverso small seconds

Lot 87, 2nd-gen Lady Reverso (black dial)

Lot 88, 2nd-gen Lady Reverso (white dial)

You might look at this and think “what the hell is a 1st- or 2nd-generation Reverso?” Let’s explore, first by taking a closer look at the first Reverso from 1931.

First generation Reverso 1931

The Reverso was one of the first wristwatches designed and serially produced by a watch manufacturer. Think about it: launched in 1931, the Reverso came a year before the Patek Philippe Calatrava 96. Because of that, Jaeger-LeCoultre didn’t have a suitable movement to fit its unique swivel-case design. In fact, Jaeger-LeCoultre hadn’t even combined into one entity. Because of these historical oddities, the first-generation Reverso has a couple of defining features:

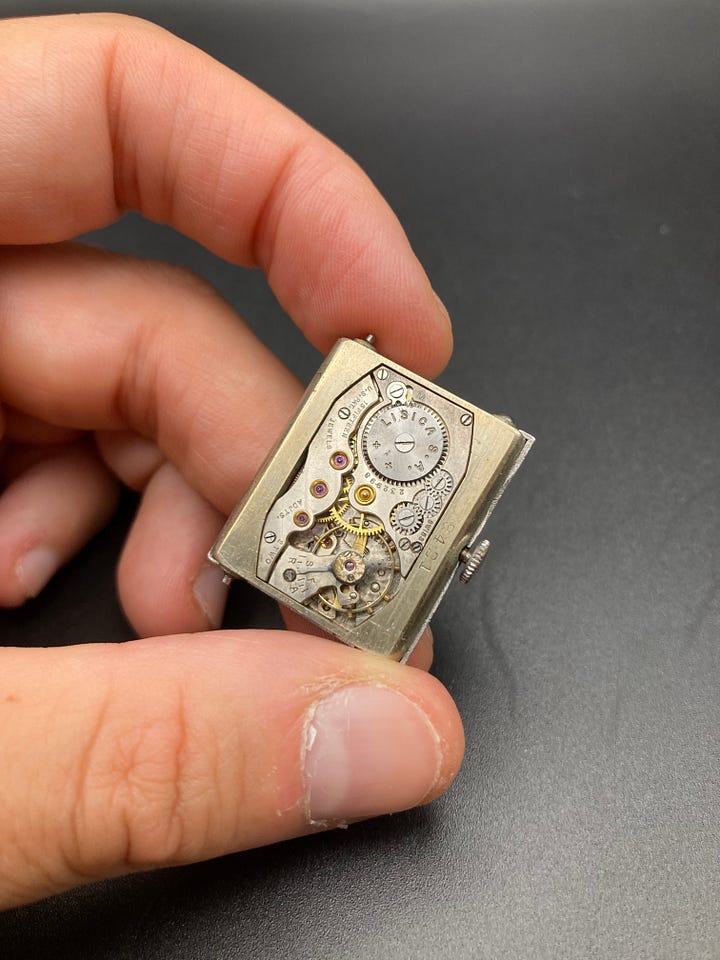

Tavannes (Lisica) movements

Reverso-signed dial, with no Jaeger or LeCoultre name

When businessman Cesar de Trey returned from India with the idea of a flipping watch for polo players, he joined forces with LeCoultre (in Switzerland) and Jaeger (in France) to create the Reverso. In 1933, those firms merged to form Jaeger-LeCoultre. It’s part of the reason the first Reversos from 1931 simply say “Reverso” on the dial.

Meanwhile, since LeCoultre didn’t have a movement fit for the Reverso in its catalog, it contracted Tavannes (aka Lisica) to produce movements for the first run of Reversos.

For me, a first-generation Reverso is the one to have. The dial is always a solid color, often black but also found in bold colors like red or blue. The simple “Reverso only” dial is clean and to the point, a statement of functionality as much as branding.

They’re also hard to find, only produced for a couple of years before the second-generation Reverso came along.

The black dial of this first-gen Reverso looks clean and original. Finarte has an estimate of €3,000-6,000. If it stays anywhere close to that range, I’d consider it a value.

Again, given their historical importance and rarity, I think Reversos – especially first-gen Reversos – are fundamentally undervalued by the market. There’s no reason a 1931 Reverso in good condition shouldn’t be a $15-20k watch, especially given the stupid prices people are paying to chase Cartier. Find it on Finarte.

Second generation Reverso

By 1933, Jaeger and LeCoultre had merged to form one firm, also owning the rights to the patent for the Reverso’s flipping mechanism. This is also when the manufacturer developed its own movement for the Reverso, caliber 410. It was a tonneau-shaped, hand-wound movement with a small seconds at 6 o’clock, also producing the modified caliber 411 with a center-seconds hand. LeCoultre also made a smaller caliber for the ladies’ Reverso.

Because of these corporate and caliber changes, the second-generation Reverso is defined by:

Jaeger-LeCoultre (or simply “LeCoultre,” mostly for the American market) on the dial

Small or center seconds

Of the second-gen examples at Finarte, the two-tone Reverso (first above) is probably the most interesting. In the early years, the Reverso was made mostly in steel, and I’ve been told it’s quite difficult to find these two-tone cases. The inner case is 14K gold, while the outer carriage is stainless steel. The silver grené dial also looks original and clean. Here’s the two-tone Reverso.

Of the second-gen Reversos, I prefer the center-seconds Reversos (example here) to the small seconds like the Reverso here with a black dial. While I love the Art Deco roots of the Reverso, the Gothic numerals often seen on these small seconds dials just feel too old. The center seconds Reversos manage to feel more modern and sporty. Here’s the second-gen Reverso.

Both of these Reversos also have an estimate of €3,000–6,000. I’d need to do more of my own research before putting my own money behind it, but the two-tone in particular is interesting.

It also shows how much the market seems to misunderstand the vintage Reverso that an auction would place the same estimate on these as it does the 1931 Reverso. Produced for only a couple of years, the first-gen Reverso should get a primo price!

Collecting the Reverso

Jaeger-LeCoultre’s The Collectibles book offers that only “a few thousand” Reverso watches were produced from 1931 to the 1950s, estimated based on the production numbers of the various calibers used in the vintage Reverso.

Collecting the Reverso is probably slowed down by a few things: (1) they’re a little small, (2) not that many were made, and (3) they’re hard to find in good condition. The cases weren’t exactly waterproof, so dials were easily damaged and reprinted or replaced. Jaeger-LeCoultre significantly reworked the Reverso case in the 1980s, upping the number of components (to 55 from 30ish) and making it more water resistant. If you’ve ever handled a vintage Reverso, you know it hardly compares to the smooth, sweet sliding of a modern one.

First series Reversos don’t come up that often. And the collectors that own them aren’t selling, either.

🏎 Bonus picks: If you’re more interested in the Heuer stuff, here’s a nice-looking Heuer Carrera 7753 NST. In the world of two-register Carreras, an NST is about as good as it gets. And speaking of undervalued: I’m not sure why people sleep on rectangular Pateks like this Patek ref. 492 (also at Finarte).

Flag and watch design, or what the hell is a vexillologist?

Finally, Illinois easily has the worst state flag in the United States. As a consolation, Chicago has perhaps the best city flag. The Illinois Flag Commission just announced its 10 finalists for a new state flag, fixing the “seal on a bed sheet” that afflicts our flagpoles.

The flag chatter reminded me of one of the best 99% Invisible podcast episodes, which looks at the best and worst flags, along with what makes for a good flag. According to vexillologists – nerds who study flags – there are five principles of good flag design:

Keep it simple

Use meaningful symbolism

Use two to three basic colors

No lettering or seals of any kind.

Be distinctive

I feel like these principles apply to watch design too? At least, I certainly think this exercise applies:

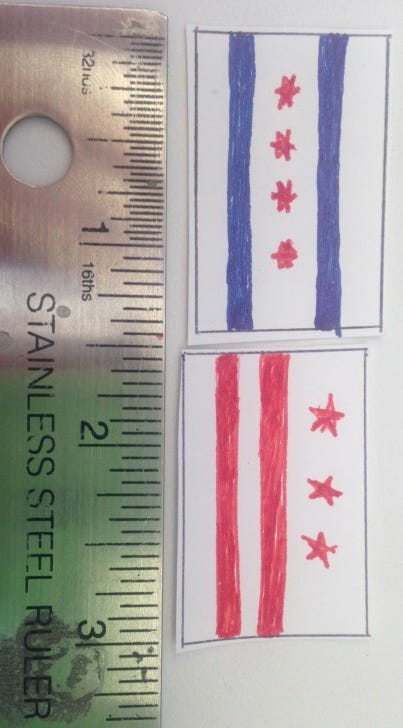

Here’s a trick: if you want to design a kickass flag, start by drawing a one-by-one-and-a half inch rectangle on a piece of paper.

A design at these dimensions held 15 inches from your eye looks about the same as a three-by-five foot flag on a flagpole a hundred feet away.

I think the same exercise works for watches. After all, most watches already measure somewhere between 35-45mm, or about the 1.5 inches vexillologists ascribe for a good flag. This is what works about Bad Art Nice Watch. For example, here’s a Paul Newman he drew. Even from a distance, it’s a Paul Newman:

Which brings me to the Watch of the Week. This drawing is actually part of the Laviolette Foundation charity auction closing just a few hours after this email is sent. Head to Christie’s to see the entire selection of watches for charity.

Keep up the good gatekeeping,

Tony

Tyler’s new album, CHROMAKOPIA: 7/10

This anti-Rolex ethos is also what I love about ‘90s IWC. It’s a vibe I’m not sure any brand can claim today – maybe Tudor can? – and feels open for the taking.

Yes, the new Monoface Reverso is actually about 1mm larger than the vintage Reverso. But the new Reverso case is so much better constructed that it’s hardly a fair comparison.

I came for those reversos (the hands!) but stayed for the lesson on watch design. I always think if you can reduce an idea to a very simple line drawing and it’s still special, then you’re onto something. Otherwise you’ve got to get the glitter out and start rolling…

When the "Problem with Provenance" popped up in my inbox I thought someone was taking shots at me! The relief that washed over me when I realised it was your newsletter!

I love provenance in watches, but I totally agree with your assessment. History is simply interesting and any impact on price should be minimal. I fear people often get carried away!