Hollywood dealer Ken Jacobs; Taylor Swift on restoring vintage Cartier

And watch spotting at MB&F's M.A.D. Gallery

Since the best type of conspicuous consumption is content consumption, we’re hitting you with a super-sized Black Friday issue. Loosen those belt buckles again, and dig in: Here are today’s articles (click these links to be taken to the full article, or just keep scrolling):

Rescapement is a weekly newsletter about watches. Smash the subscribe button to get it delivered straight to your inbox every weekend:

Interview: Hollywood dealer Ken Jacobs of Wanna Buy A Watch?

Ken Jacobs started Hollywood vintage watch store Wanna Buy A Watch? in the early 1980s. Talk to the guy, and you’d be surprised to learn he’s been in the business for more than 40 years. The youthful energy and passion he still has for watches bursts out of every sentence, perhaps most eagerly when he’s talking about his own collection.

Ken got into watches after earning his PhD in clinical psychology and working in the field for a few years. After a childhood of collecting and an early adulthood spent going to the Rose Bowl Flea Market to trade coins, he discovered watches, first being drawn in by early 20th-century pocket watches.

“The lightbulb went off — these things are valuable — beautiful, functional, and historical,” Ken said. “I thought ‘I’m moving out of coins, which are two-dimensional and static, to watches, which are 3-D.’”

Ken’s stories take the history of watches and watch collecting that you usually only read about and bring it to life, from a guy who happened to live it all.

In this interview, we talk about his years as a dealer and then get into a bit of his personal collection.

Q: Let’s do a quick intro to Ken Jacobs. Who are you and how’d you get into watches?

Ken: I have my PhD in clinical psychology, which has nothing to do with me in the watch business, but I spent a good number of years doing that.

I’ve been a collector all my life. It’s all about the collecting gene. As a kid I collected seashells, I had a stamp collection. I got deep into being a coin collector. I was the kid who, in junior high, would take the bus to the bank and exchange a $20 bill for a roll of pennies and dimes and look for better dates, better examples, and continue to do this until I was exhausted or out of money.

How did that collecting lead you to watches?

After grad school in Chicago, I moved out to California to do an internship in clinical psychology and started going to the Rose Bowl flea market, selling coins.

I ran into a UCLA student who was selling pocket watches, mostly hunter case watches. They were beautiful, fascinating, and I thought it was just great value. He was selling them for maybe $125 or $150 — beautiful Elgin, Waltham solid gold watches. The lightbulb went off — these things are valuable — beautiful, functional, historical. I thought ‘I’m moving out of coins which are two-dimensional and static, to watches, which are 3-D.’ So I moved out of buying and selling coins to pocket watches, a far more interesting object.

How has the watch space changed since you started?

In the early days, guys had rolls of gold watches, electric watches, often from American brands like Hamilton or Elgin, and they’d be proud of and celebrate and wear different ones every day — rose gold, yellow gold, different straps, mostly rectangular.

In the late 80s or 90s, the sports Rolexes — GMTs, Explorers would cost $1500 to $2000. Daytonas were $500 when I started and would sit unsold. The first Paul Newman Daytona I sold may have been $6500. A shift began when collecters began consolidating their collection of 10, 20, 30 American wristwatches into a couple Rolex Bubblebacks and more valuable and prestigious pieces. There was a huge shift towards Rolex and Patek.

Nowadays, it’s Rolex, Rolex, Rolex, with Omega a distant second and Cartier third.

Do you ever miss those old old days?

Not necessarily, it’s just a shift. When you have a history of 40+ years in the business, you know about these things because you’ve lived them, not because you read about them or watched a documentary.

Am I the most knowledgeable about watches among vintage dealers? Certainly not, but I do have years of first-hand experiences of living that goes beyond studying and reading.

Let’s hear a bit about your personal collection. What do you like to collect?

I’m really drawn to good design. That really is the strongest driver for me. Those square gold watches, it was all about design. Now, I’ve shifted into the mid-century design aesthetic. 30 years ago I started paying attention to these designs and I started referring to them as hipster designs, when all the juice was in those 1920-30s watches. But the watches from the 50s-60s just had a slicker design. And I thought, ‘I have to buy some watches for the hipsters.’ Well, the hipsters have turned into mid-century modern, and it’s all these fantastic 50s, 60s, and 70s designs.

👉 Check out our full interview with Ken Jacobs for more stories and a closer look at his personal collection

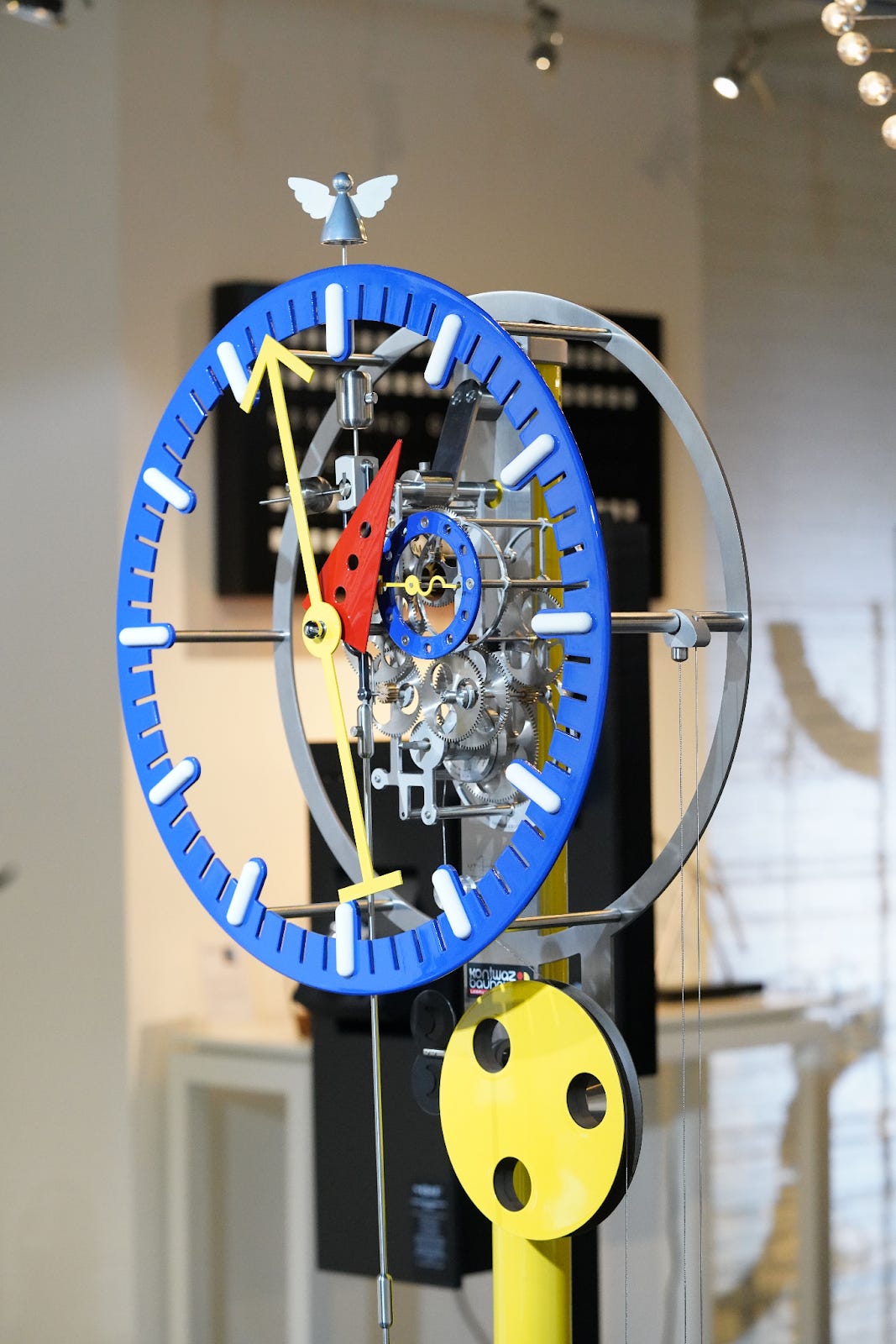

Watch spotting at MB&F’s M.A.D. Gallery

By: Charlie Dunne

On a recent trip to Geneva, Continental correspondent Charlie Dunne popped into MB&F’s M.A.D. Gallery for a look at the kinetic art and horological objects of Max Büsser and his Friends. He gives us a look at what he saw, through his camera lens.

👉 See the full photo report here.

What Taylor Swift can teach us about restoring vintage watches

And what is a restored vintage Cartier worth?

Back in April, we ran the story of the Cartier Tank Cintrée gifted by actor Fred Astaire to English jockey and horse trainer Felix Leach Jr. Astaire gifted a beautiful, bold Cintrée to his friend, Leach Jr., likely on the birth of his first child, engraving the case back “Felix from Fred ‘29.”

The Leach/Astaire Cintrée is basically one-of-a-kind, set apart by its dial, featuring large, luminous Arabic numerals. On the already bold Cintrée, which measures 46mm from lug to lug, the luminous numerals — and cathedral hands — have a striking effect.

At some point in the past few decades, Cartier acquired, and eventually restored, the Leach/Astaire Cintrée. We know this because it first appeared at auction in the 1980s with the original, badly patinated dial.

The numerals, originally radium, were faithfully restored, not with lume, but with paint. The restoration was likely done for aesthetic reasons back then. As Charlie Dunne wrote in that piece:

In the period of its sale, the adamancy for untouched cases and original dials was not as pronounced as it is today. The Cartier image and perception is very much one of refined luxury. This brand image differs from say, Longines, which might embrace a ‘damaged dial’ due to the fact these timepieces were true tools. So this raises the question of whether the decision was appropriate in hindsight.

In regards to a watch such as this Cintrée, undoubtedly we will see polarizing viewpoints. While the argument could be made that the dial, in original condition, did not fit within the Cartier aesthetic, the counterargument would strongly appeal to the importance of preservation.

Charlie points to a potential alternative restoration approach: When Vacheron Constantin restored the rare “Don Pancho” minute repeater, which had a similarly damaged original radium dial upon its discovery, the original dial was preserved and sold along with a manufactured replacement dial to allow the option for the watch to remain as original as possible.

After that article, a collector actually reached out to us, sending a few photos of a Tank Cintrée in white gold with the same striking dial as the one gifted by Fred Astaire. As that individual explained, this dial was also faithfully restored by Cartier in the past few years.

On Thanksgiving, that same watch, a white gold Cartier Tank Cintree with luminous Arabic numerals sold for about $290k at Phillips Hong Kong. The catalog entry makes heavy reference to the Leach/Astaire Cintrée, saying that example is the only known luminous dial in yellow gold, and this example at Philips is the only known in white gold.

Here’s how Phillips describes this watch’s restoration in the catalog entry: “For two years, the watch was left in the dedicated hands of its maker with instruction to restore the dial, hands and case based on the original archive of Cartier with the techniques used in the 1930s, with the only exception being the use of modern luminous material as opposed to radium.”

Not a cheap restoration, in other words.

No doubt, it’s an extremely rare and important watch, and it’s exciting to see the example come to auction a few months after our article about a similar example.

But the question remains: What’s the proper way to treat these old, damaged watches (especially those with radium dials)?

Listen, it’s the (perhaps unfortunate) reality that many of these beautiful watches will need to be restored to be considered “collectible” by modern standards. The Cintrée examples we’re talking about here are nearly 100 years old, and looking at the unrestored version of the Astaire/Leache Cintrée above, there’s no way that watch sells for nearly $300k like this restored example did.

I remember it all too well

Now for the “what can Taylor Swift teach us about watch restoration” portion of today’s ‘sletter. For those who have retreated from the world, Taylor has been re-recording and re-releasing her first six albums so that she can reclaim full ownership of her music catalog. This month, she re-released Red (Taylor’s Version), featuring the exact same tracklist as the original album, along with a few bonus tracks “from the vault.”

The re-released Red is an exact re-creation of the original album, along with a few aesthetic flourishes (anyone else still crying from the 10-minute version of “All Too Well”?). It’s Taylor reclaiming her history and “restoring” it to make it enjoyable (not to mention profitable for her) for years to come.

Cartier’s (and other manufacturers’) restoration of their vintage watches isn’t dissimilar from Taylor’s re-recording of her classic albums. It’s Cartier reclaiming its history by restoring — in what it feels is a faithful way — so its original designs can continue to be appreciated for years to come. If Cartier didn’t go through the effort of restoring this Cintrée, it’s unlikely anyone pays much attention to it, or that it sells at auction for $300k, blowing past its $40-80k estimate. Even worse, the watch might end up terribly restored by some other third party, completely losing its historical connection to the Maison.

When we spoke to the TrueDome creators — the guys going through the painstaking process of re-creating vintage acrylic Rolex crystals — one thing they said stuck out to me. They said their goal was to arrive at a crystal that allows the watch’s design to be appreciated the way its engineers originally intended.

To me, that’s the true beauty of these things. Not the aesthetic beauty in and of itself. Lots of things are aesthetically beautiful. It’s the beauty of appreciating an object as it was originally designed and created, all those years ago. Yes, this allows some room for faithful restoration. But it also makes one appreciate all the more when an old object like this is found in completely original condition.

Rescapement is a weekly newsletter about watches. Smash the subscribe button to get it delivered straight to your inbox every weekend: