The Uncelebrated Timepieces of 'A Grand Complication'

Tiger Woods and the Tudor 'Tiger' Chronograph

This week, a guest post from Charlie Dunne. He takes an in-depth look at the underappreciated timepieces from two of the 20th century’s greatest collectors, Henry Graves Jr. and James Ward Packard. Then, get your golf fix with my look back at the Tudor Tiger Chronograph. -Tony

Coins, canes, and complications: the uncelebrated timepieces of Graves and Packard

By: Charlie Dunne (@books_on_time)

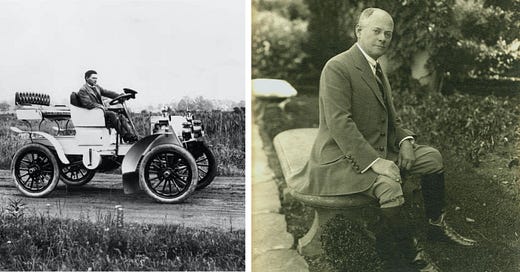

What are the first watches that come to mind when you hear the name Henry Graves Jr. or James Ward Packard? Undoubtedly, one’s mind gravitates towards The Graves Supercomplication and The Packard. The two collectors have been immortalized within the watch community as the most prolific watch enthusiasts. And while the duel is somewhat summed up by these two complicated watches, the evolution of their watch collections paints a much broader picture of their pure love of horology. In that, it is the under-acknowledged timepieces associated with the two men that may warrant a bit more discussion. The most comprehensive research into the two men can be found within Stacy Perman’s 2013 book A Grand Complication. It is worth highlighting these lesser-known timepieces to better appreciate the manner in which these two collectors pushed Patek Philippe (and other manufacturers) to new heights during the early half of the 20th century.

Desk clocks

While 2020 was the year of the travel clock, nearly a century ago one of the most iconic desk clocks would be commissioned. James Ward Packard’s patronage had resulted in him becoming a highly valued client of Patek Philippe. As a show of its appreciation, the manufacturer “rewarded” him with a double-barrel desk clock. The clock features a perpetual calendar, moonphase, and an 8-day power reserve. Referred to as “Le Presse-papiers” this objet d'art served as both a desk clock and paperweight. It also housed a secret compartment underneath for storing small personal mementos, along with the winding key. Packard paid 5,275 Swiss francs for the timepiece and it became the marvel of his office desk in 1923. As with most of the important, bespoke timepieces, both Packard and Graves were very insistent that the manufacturer go an extra step in personalizing the work upon completion. In this example, the inlaid blue enamel J.W.P monogram was adorned atop of floral decorated engravings. Both the movement number and year of acquisition can be seen on the dial.

Packard’s Patek desk clock

Graves Jr.’s Patek desk clock

Many have noted that Packard and Graves Jr. both, in a sense, sponsored the Patek Philippe during periods of economic hardship. As mentioned earlier, this loyalty to the manufacturer had its perks in the form of “rewards”. However, it’s important to distinguish this from a transactional contract and instead recognize the relationships built between the patron and artist. Yes, a loyal client of their status would be granted a level of creative input (occasionally the line would be drawn for less tasteful client requests such as J.B. Champion’s “Happy Hour”), but the tradition of relationships has been maintained beyond the founders’ ownership. In the modern era, we see these in instances such as eligibility to acquire Rare Handcrafts or a more subtle personalized dial. In 1927, Henry Graves Jr. took possession of the second desk clock made by Patek Philippe. Known for his hands-on relationship with Patek and his love for personalization, this clock distinctly features the engraving “Made for Henry Graves Jr., New York”. This, along with Packard’s desk clock are the only two of their kind. The timepiece would have been deeply sentimental, as his collecting habits included French paperweights among various other forms of antiquity. Interestingly enough, Graves received this desk clock the same year his contemporary would acquire “The Packard”.

Horological paraphernalia

Considering the family business of Maxwell and Graves was a banking firm, a watch cased within a coin would seem to be quite appropriate for Graves Jr. Yet his professional interest in finance crossed over into a different form of collecting. In addition to timepieces, Stacy Perman describes an “extraordinarily comprehensive collection of rare coins” while contextualizing the man beyond the watches. He was a collector of so much, yet his horological instruments outshine any competing possessions. This commissioned piece was manufactured in 1925 and sold three years later. In line with his exclusive nature, this was one of the earliest coin-form watches made by Patek Philippe, and would go on to inspire an entire line of coin watches. The tails side of this $20 coin features an eagle, which ironically is symbolized within the most sought-after watches belonging to the collector. The Graves' family Coat-of-Arms includes the quote “Esse Quam Videri” (To Be Rather Than to Seem) below an eagle, which can be inferred as a clue to the family’s favorite vacation destination, Eagle Island. It is important to note the context of the coat of arms, as Graves Jr. was very much adamant of personalization to his important timepieces.

Packard also enjoyed a horological accessory that would serve to only be enjoyed on a personal level. Many collectors cite a certain understated elegance that attracts them to Patek Philippe. The ability to enjoy a fine timepiece without having to broadcast it is something that is within the DNA of the company. We see this has been a principal for over 100 years in Packard’s sterling silver watch that additionally functioned as a handle for his outdoor excursions. One thing that separated Packard from later collectors was his engineering background. His desire to create concepts for functional timepieces made his approach a more collaborative relationship. As Stacy Perman put it “men like Ward built automobiles and men like Henry Graves Jr. bought them”. This is not to say that other collectors lacked creativity, but more so to highlight Ward’s ability to visualize an engineering project and challenge the greatest manufacturers to push their boundaries. The walking stick watch and several other custom timepieces within his collection were acquired through Patek’s American agent. All were “designed as homages to art and science”.

Complicated Vacheron Constantin timepieces

Packard’s affinity for Vacheron Constantin was quite strong during the latter portion of the 1910s. He had taken ownership of three of his first four Vacheron Constantin watches during the period of 1917-1919, and ended the decade with a particular special timepiece. In addition to being a chronograph, the watch featured a unique set of repeater functions. The watch incorporates a trip repeater, grande and petite sonnerie, and a half-quarter repeater. All of these will indicate the time increments upon the hour in a different tone. This arrangement of complications was described at its public auction as being the only time the manufacturer had completed a watch of this caliber. Just four months after Packard’s passing, the complicated Vacheron, along with several others, was bequeathed to his nephew Warren. One year after the acquisition, Warren would tragically die in an aviation accident, leaving the watch unattended in a safety deposit box for over six decades.

During a recent panel discussion with WSW, Patek Philippe expert John Reardon mentioned that in his experience, Patek Philippe collectors often have a breadth of watch brands they appreciate. Graves Jr. and Packard were no exception to this. Long before watch marketing became integrated into our daily lives, collectors would have to have been more astute. While there were certainly marketing efforts in the form of establishing relationships with esteemed retailers, newspaper ads, and mail, the recognition of quality work and watchmaking acumen would have been much less influenced by outside entities.

Graves Jr.’s interest drove him to collect masterpieces from George Graham, Thomas Tompion, and many more names of the highest prestige. Yet one of the more recognizable watch names associated with Graves Jr. was Vacheron Constantin. Before Patek Philippe and Vacheron Constantin were anointed as part of watchmaking’s “Holy Trinity”, both Graves Jr. and Packard were able to recognize manufacturers capable of creating instruments of the highest complexity. It is fair to say the collectors played a vital role in establishing the reputation the two companies enjoy to this day. Perman adds interesting context to the discussion of provenance within the world of horology. We are often fascinated by who wore a watch, whether it be a celebrity, photographs from the past, or a public sale at auction. Yet it is not only the collectors who seek to elevate their status associated with popular figures, but also the watchmakers themselves. In an interesting turn of events, the folklore surrounding one First Prize Observatory tourbillon chronometer exemplifies this.

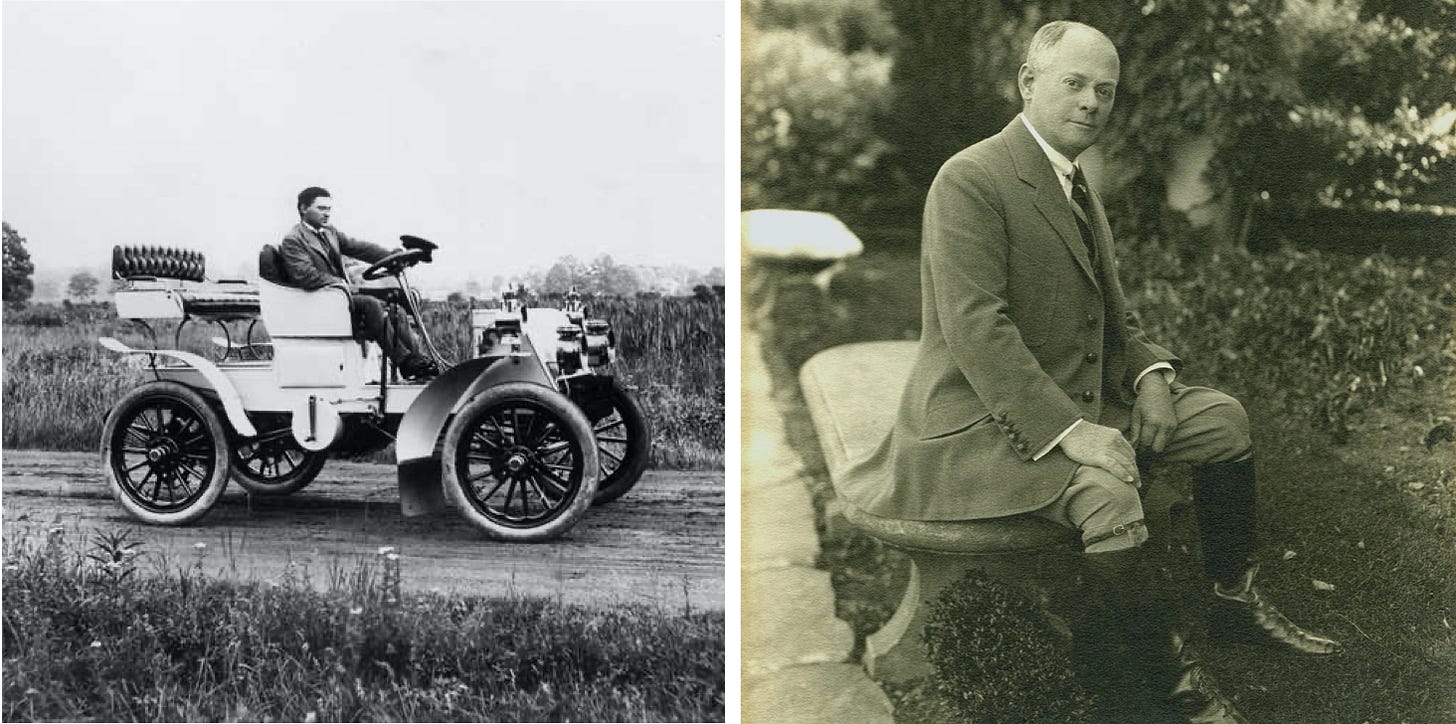

First Prize Observatory tourbillon chronometer

Correspondence in 1928 with Vacheron indicates that a First Prize Chronometer at the Geneva Observatory was sold to Graves Jr. on a trip to Europe. During the 1990s, while the reputation of both collectors was gaining momentum, talk of Graves' Vacheron Constantin began to circulate. At Sotheby’s 2002 ‘Property from the Estate of Esmond Bradley Martin’ auction, a First Prize Chronometer from the manufacturer sold for $295,000. The aftermath of this sale allegedly involved various trades for larger amounts. Rumor had it that the watch had belonged to the prominent collector and that it had even featured the Graves coat of arms. Eventually, Vacheron Constantin stepped in and paid a reported $2 million bounty to secure the watch. However, sometime after the Sotheby’s sale, contention surrounding the claims of the Graves coat of arms began to develop: some stated that it was manipulated, others that it was never observed. Nevertheless, Perman’s correspondence with a Vacheron representative indicated the timepiece “was destined for Henry Graves Jr., but Vacheron Constantin finally kept it for communication/promotion purposes” and acknowledged the watch was sold in the 1950s without Graves' coat of arms. Additionally, the lot essay indicates that the controversial watch actually won first place six years after the recorded 1928 rendezvous. While the purported engraving and/or disappearance cannot be accounted for, it is worth mentioning that at the time of the Sotheby’s auction, there was no indication of provenance and it certainly would have been a noteworthy feature to both the auction house and bidders.

The next chapter

All of this raises the question as to the current whereabouts of the 1928 First Prize Observatory Chronometer Vacheron Constantin with movement number 401562 (the confirmed VC that was ordered by Henry Graves Jr. that has never surfaced publicly.). This mystery illustrates how much is still to be learned about Graves Jr. and Packard, particularly by studying some of the lesser-known pieces from their collections.

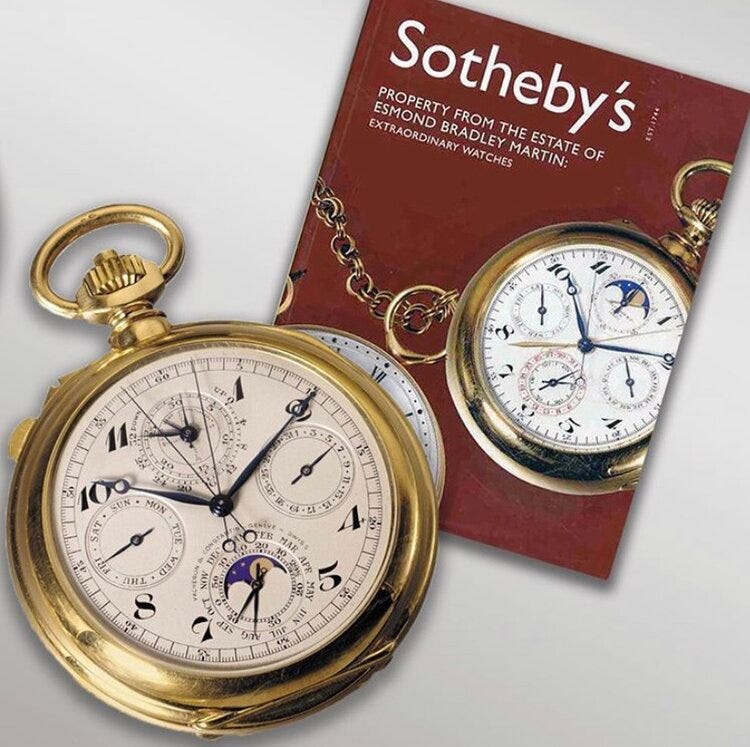

Another such mystery is the Patek Philippe “mystery box”, a box from the manufacturer customized for Graves Jr. It’s an empty box, containing only papers with case and movement numbers, as well as drawings for a complicated astronomical watch. The box is identical in size and shape to the box in which the Graves Supercomplication was delivered to the collector. Despite directly being told that the mysterious Patek Philippe watch belonging to this box does not exist by the late Pete Fullerton (the grandson of Henry Graves Jr. and a prolific watch collector in his own right), John Reardon remains adamantly optimistic of finding such lost treasures.[1]

These artifacts, whether lost to time or waiting to be discovered, give the watch community something to anxiously hope for. Perhaps the next chapter is just waiting to be written. Only time will tell.

When asked about the impact A Grand Complication has had on elevating the collections of Packard and Graves Jr., Reardon said: "Perman is without a doubt one of the best writers in the world today. Her ability to research, ask the right questions, and dig deep into the heart of a question is brilliantly reflected in her work. A Grand Complication delves into the minds of two of the greatest watch collectors of the 20th century, James Ward Packard and Henry Graves, Jr. Her words eloquently entertain as she introduces the reader into another world of wealth, privilege, and obsession.”

A Grand Complication: The Race to Build the World’s Most Legendary Watch by Stacy Perman is available to purchase here, and on Amazon.

Acknowledgments: I would like to acknowledge the wonderful work of Stacy Perman. This book is a must read for anyone who has the slightest fascination with Patek Philippe. Additionally, a huge thank you goes out to Eric Wind for recommending this book. The encouragement and guidance is sincerely appreciated. This article could not have been completed without the incredible support and guidance from John Reardon. I am humbled by the enthusiasm he has shown in my interest to learn.

A tradition unlike any other

In honor of this week’s Masters, a throwback to an article I published earlier this year about the relationship between a young Tiger Woods and Tudor. While I say that I’m personally offended by the way Tudor/Rolex did Tiger, it turns out that Dustin Johnson, today’s likely winner, is a Hublot ambassador. So I guess it wasn’t that bad for Tiger.

Tiger Woods and the Tudor Tiger Chronograph

When Tudor pulled out of the U.S. market around 1996, Tiger Woods was just announcing his professional arrival. I’ll save the hagiography for another day, but let’s put it this way: one of my first conscious memories as a kid was watching Tiger run away with the 1997 Masters. Like, do you know how big of a deal it has to be for a kid to still remember some golf tournament on TV 20 years later?

When Tiger burst onto the scene, Tudor quickly came knocking. Shortly after Tiger won that first Masters in 1997, he struck a $7 million sponsorship deal with Tudor, becoming a spokesperson for the brand and can be seen wearing its series of Oysterdate chronographs. Tudor even added Tiger’s name to this collection of chronographs, also making a series of limited edition models featuring especially brightly-colored “exotic” dials. These exotic dials don’t command a premium like many other exotic Tudors do, but with John Mayer launching the humble green dial “Christmas” Daytona into the stratosphere last year, perhaps Tiger’s green dial Tudor should.

Then, in what’s got to be one of the greatest branding slip-ups since Kendall Jenner solved everything with a Pepsi, Tudor and stablemate Rolex let Tiger get away. In 2003, by then at the pinnacle of not only the golfing, but also the entire sporting world, Tiger inked a deal with Tag Heuer. He’d stay on board with Tag Heuer until 2011, when the brand decided not to renew his contract because, well, you know.

With Tiger down and out, this time Rolex jumped at the opportunity to bring him on board as a Rolex ambassador. It was a sponsorship that always should’ve been, and finally was; it was only fitting that, when Tiger slipped on his 5th green jacket in 2019 he was wearing a Rolex Deepsea.

Rolex, as the brand itself is keen to remind you, is for winners. With Tiger on the verge of becoming the winningest golfer of all time, it only makes sense that a Rolex remains on his wrist. Besides perhaps Swiss Roger Federer, Tiger just seems like the most natural fit of any modern athlete to be a Rolex sponsor.

Even back in 1997, we knew Tiger was a prodigy. He’d dominated junior golf like no one, ever, and with a certain charisma that had certainly never been seen on a golf course. It’s always struck me as peculiar that Rolex took a look at Tiger and said, “I’ve got a great idea! Let’s use this once-in-a-generation figure to refocus our lower-priced sub-brand at younger consumers.” This was after Tiger had already signed a deal with Nike valued at $40 million, so it’s not like Rolex would’ve been going out on a limb to make Tiger the face of the Rolex brand.

This is all to say that I’m personally offended by the way Tudor and Rolex did Tiger, so perhaps it wasn’t surprising he jumped ship in 2003. But before that, the pair managed to make a series of curious chronographs together.

Read the full article for a look at the Tudor ‘Tiger’ chronograph collection.

—

[1] Watch John Reardon discuss his journey to discover the watch belonging to the Graves Jr. “Mystery Box.”

Rescapement is a weekly newsletter about watches, bringing horological secrets vintage and modern to your inbox every Sunday.