Here at Rescapement, we usual publish our weekly newsletter over the weekend. But, some stories are just too good to wait. This story — involving one of the most historically (and legally) important Rolexes in history — is one of those stories. I implore you to head over to Horolonomics right now to read the full story of The History of the Radioactive Rolex with One Complication. Check out a teaser below, but you’ll want to head over to the full article to see how this one ends(?).

Many likely know the story of the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission’s discovery that 13 watch companies in the U.S. had imported luminous material with stronium 90 — a waste product from nuclear fission — during the 1950s. Among others, the findings implicated Rolex’s first GMT-Master reference 6542. As Professor Brendan Cunningham writes in his article on Horolonomics:

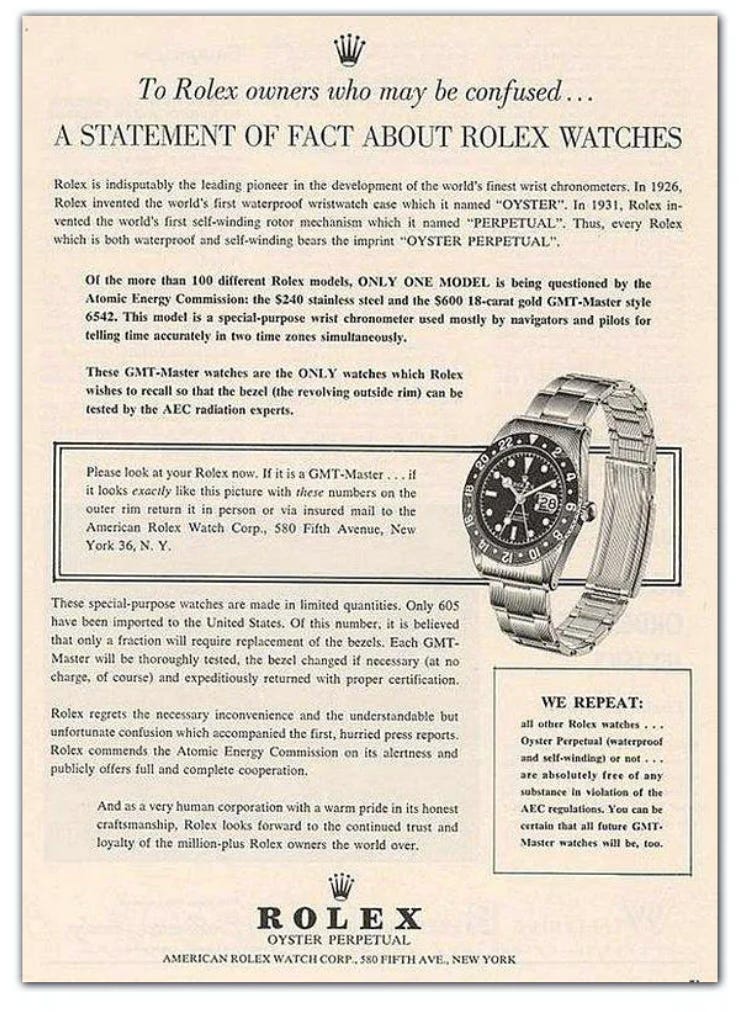

Rolex was one of the companies notified by the AEC that a GMT-Master purchased in Singapore contained strontium. It embarked on a nationwide search to reclaim this reference. The AEC licensed Rolex’s headquarters in New York City at 580 Fifth Avenue to receive watches and, under supervision of a commission inspector, test them for strontium. Out of 250 watches received, approximately 185 were hazardous and required replacement of radioactive parts.

Rolex advertised this process and encouraged owners to participate. Some time later, in Tokyo, Japan, news of this hazard reached a GMT-Master owner. Michael Williams was a British diplomat. At the time he served in England’s Tokyo embassy. He had bought a GMT-Master, also in Singapore, in 1960. Michael was fastidious about time so he appreciated the accuracy offered by a fine Swiss watch. The GMT complication also allowed him to keep track of time in Manchester, England, where his family resided while he was working abroad. He grew concerned that his family of five may have been exposed to radioactivity while he was home for an extended period of time during the holidays. I learned that Michael was not fond of attorneys but, given the potential harm to his wife and young children (two sons and a daughter), he contacted a lawyer to learn more about his options.

This is where Brendan’s digging began, as any trace of Williams’ lawsuit against Rolex has largely disappeared over the years. He writes:

I’d assumed that Rolex had somehow gained possession of the GMT-Master in question and asked Edward if this was the case. “No,” he said, “I know exactly where the watch is.” I think my heart skipped a beat. A vintage watch’s value is determined by a set of factors. One is rarity. Because this particular reference was “recalled” and altered, examples in original condition are undoubtedly hard to come by. Another factor is provenance: does the watch have historical significance and a documented connection to the original owner? It sure seemed like this was the case.

Edward explained that after his father’s death the family gathered in Manchester for the funeral and the reading of his father's will. At some point the family emptied a storage unit and, Edward related, “we found the watch in the very back in a box.” Later, after the reading of their father’s will, Edward’s older brother Andrew offered to drive to their next destination. They had placed the watch in the car. Andrew abruptly announced, “I know what I’m going to do with that watch.” Without consulting Edward, he pulled over the car after crossing a bridge over the River Irwell. He grabbed the watch and they both exited the car. Andrew threw it into the river.

So there it is: Perhaps the most important Rolex GMT-Master in history, at the bottom of a river, lost to history, right?

Wrong. This is where the story really begins.

Head over to Horolonomics for a watch thriller that James Patterson will surely be adapting into a novel soon.