Collector's Guide: The Chopard L.U.C 1860, and Making One of the Best Automatic Movements Ever

How Chopard produced the caliber 1.96 and the original L.U.C 1860 during the rebirth of watchmaking in the 1990s.

[Ed. Note: This article was originally published on Subdial in 2022. Subdial has since updated its website. With their permission, I’m republishing this article in its entirety here. It’s one of my favorite articles about one of my favorite watches, and contains exclusive info from Chopard’s former Heritage Director, Juan Garcia, who sadly passed in 2023.]

The list of automatic movements that might seriously claim the title of “ best automatic movement ever produced” is short. Ask around and you might get answers like the Patek Philippe 27-460, the brand’s second automatic caliber; the Jaeger-LeCoultre caliber 920 (adopted by Audemars Piguet, Patek, and others, and used in the original Royal Oak and Nautilus); or legendary calibers from Rolex and Omega.

But one credible answer comes from a manufacturer that might surprise some: The Chopard L.U.C. caliber 1.96.

A (very) brief history of Chopard

Watchmaker Louis-Ulysse Chopard founded Chopard in the Swiss Jura in 1860. Over the next century, Chopard became known as the height of elegance and luxury, becoming mostly recognized as a jewelry house. Until the 1990s, its most recognizable contribution to horology was its “Happy Diamonds” watch line, a design featuring diamonds “floating” between two pieces of sapphire glass on a watch. Beautiful watches, to be sure, but more in the tradition of Chopard as a jewelry maker than a watchmaker. Surely, no one would have expected the house of Happy Diamonds to go on to produce one of the best modern automatic calibers.

In 1963, the Chopard family, which had held the company since its founding, sold the family business to German goldsmith and watchmaker Karl Scheufele. By the 1980s, Schuefele’s son, Karl-Friedrich Schuefele (at Chopard they call him “KFS,” so we’ll do the same), took the helm at Chopard. At the time, Chopard was manufacturing some of its own watch components, but it was sourcing primarily from third parties.

Siblings and co-presidents of Chopard, Caroline and Karl-Friedrich Schuefele.

“The 1990s were a bit of a make-or-break moment for many Swiss watch brands, Chopard included,” Chopard Director of Patrimony Juan Garcia said of the era.

KFS believed that Chopard was duty-bound – both by Chopard’s and his father’s origins as watchmakers – to become a manufacture that could produce its own movements completely in-house, rivaling Switzerland’s other historic houses. KFS also believed that, nearly two decades removed from the origins of the quartz crisis, mechanical watches were destined for a renaissance.

Developing the L.U.C. caliber 1.96

According to Chopard: A Passion for Excellence, KFS began organizing around his mission to turn Chopard into a true manufacture in 1985, bringing together a skunkworks of watchmakers, engineers, and technicians within the company to lay the foundation for a new mechanical caliber.

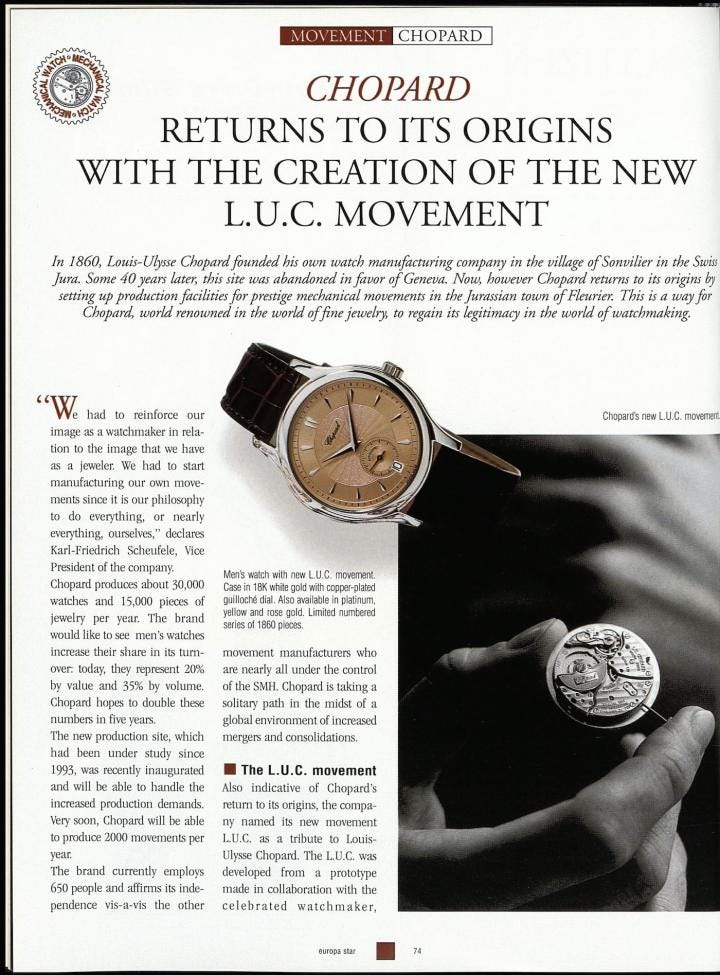

Louis-Ulysse Chopard had founded his watchmaking company in Sonvilier, Switzerland, so when KFS decided to build Chopard Manufacture, it made sense to return home. In 1993, Chopard launched its efforts to become a manufacturer, first by enlisting the help of master watchmaker Michel Parmigiani. The collaborative project set up shop in Fleurier, just 40 kilometers from Chopard’s historic home in Sonvilier.

“I wanted to create a special, dedicated entity because it was obvious to go any further, we had to build a unit to produce ébauches,” CEO Karl-Friedrich Schuefele told Europa Star in 2021. For Chopard, the goal was independence, to create a movement on par with other historic Swiss manufacturers. KFS wanted a new caliber that would be highly reliable, feature a micro-rotor and large power reserve, as well as a beautiful caliber, finished to the highest degree. He also wanted a movement that could be easily modified by adding complications so that Chopard’s fine watchmaking could grow.

With its brief in hand, Chopard’s team and watchmaker Parmigiani got to work on the ASP (Association Scheufele Parmigiani) caliber. However, after a couple of years of development, the team was still having trouble with the winding efficiency of the movement. At that stage, KFS decided to sever ties and bring the team fully in-house. Chopard began renting workshop space in Fleurier and setting up its own manufacture (fun fact: a young Jean-Frédéric Dufour, now the CEO of Rolex, was charged with organizing the manufacturer). For nearly four years in all, engineers, technicians, and watchmakers toiled in Chopard’s high-tech workshop to create an automatic movement that rivaled Switzerland’s best.

Finally, in December 1995, the definitive version of KFS’s vision was delivered in the form of 20 prototypes of the caliber 1.96. The resulting caliber was a 27mm (12 lignes) movement that could be precisely regulated to chronometer standards, featuring a micro-rotor that wound two mainspring barrels and featured a 70-hour power reserve.

Some of these prototype movements were eventually fitted into a stainless steel case with a simple dial, belying the beauty that would soon follow for the first production wristwatch featuring the caliber 1.96. Visit the Chopard manufacturer and you might have the opportunity to see an early prototype in the metal.

The caliber 1.96 is most commonly compared to Patek’s caliber 240 micro-rotor, but is arguably finished to a higher degree. Either way, it’s a more affordable and accessible representation of fine Swiss watchmaking.

By 1996, Chopard was ready to put the caliber 1.96 – by now officially named such in reference to the year it was completed – into commercial production with the L.U.C. 1860, named after Chopard’s founder and the year he founded the company.

A technical look at the caliber 1.96

Before looking at the L.U.C. 1860, we must further explore the caliber 1.96.

Respected writer Walt Odets wrote, “[f]rom the standpoint of both design and execution, the caliber 1.96 is probably the finest automatic movement being produced in Switzerland.” Early blogger and respected collector SteveG shared similar sentiments. So what made the caliber 1.96 so good?

First, there’s the fact that it’s one of the most beautiful movements this side of the Patek Philippe Seal. Let’s start with the certifications: the caliber 1.96 is COSC certified, attesting to the caliber’s accuracy. It also carries the Geneva Seal (Poinçon de Genève), certifying the movement’s quality of craftsmanship and finishing.

To let the numbers tell the story, the caliber 1.96 measures a mere 3.33 millimeters in thickness, featuring a beautiful guilloche 22 karat gold inset micro-rotor. The rotor winds stacked twin barrels that operate in series, which improves the accuracy of the watch over its 70-hour power reserve. It uses 32 jewels and beats at a healthy 28,800 beats per hour.

From a technical perspective, a few of the most important features of the caliber 1.96 are its Breguet overcoil hairspring and swan neck regulator. Breguet overcoil hairsprings are designed to improve the concentricity (centering) of the hairspring by letting it “breathe” on both sides (as compared to a flat hairspring, which only breathes on one side); it is also more difficult to manufacture than the more commonly used flat hairspring. This in particular helps with variation (i) throughout the watch’s 70-hour power reserve and (ii) between horizontal and vertical positions.

When Odets tested his caliber 1.96, he noted the accuracy on his COSC certificate measured an average daily variation of only 1.6; even more remarkable was the tested variation between horizontal and vertical positions – only 0.3 seconds. This type of consistent performance is attributable to the Breguet overcoil and precise hand-adjusting of the caliber.

By including a Breguet overcoil, Chopard put the 1.96 on par with another revived watchmaker, A. Lange & Sohne, which used a Breguet overcoil in its early movements, for example in the original Lange 1’s caliber L901.0. Both manufacturers would largely transition away from the feature in future production.

Speaking of German watchmaking: the caliber 1.96 also featured that swan neck regulator, a component now most closely associated with German watchmakers, in particular Lange. While it once allowed for micro-adjustment of the hairspring, now it is mostly aesthetic in nature, the long, curved neck adding to the romance of the movement.

Enough of the technical details. You don’t need to understand overcoils and regulators to know that the caliber 1.96 is absolutely beautiful. The plates and bridges are exquisitely finished, with Geneva stripes and hand-finished anglage. Even the unseen components are finished by hand – the date wheel and baseplate are both hand-finished, with an artisan applying 1,400 circular graining marks to the baseplate.

“Seeing the 1.96 movement working smoothly was one of the most emotional moments of my life,” KFS said. Sure, the caliber was beautiful, a technical marvel. But to him, it was more than a mechanical movement; his vision had been realized, and he’d brought the legacy of his father, and of L.U. Chopard, back to life.

The L.U.C. 1860

After perfecting the caliber 1.96, Chopard continued to spare no expense in developing a wristwatch for its mechanical masterpiece.

“Nowadays, the First Series L.U.C. 1860 is the grail of Chopard,” Director of Patrimony Garcia said.

Every single component of the wristwatch is gold (or precious metal, in the case of a platinum example): case, dial, indices, and hands. Owing to its history as a jewelry maker, Chopard is one of the few watchmakers performing its own gold casting in-house, meaning it produces its own alloys.

Any discussion of the L.U.C. 1860 must start with the dial. Dial-maker Metalem produced the beautiful hand engine-turned dial for Chopard, the same manufacturer that would soon produce dials for Philippe Dufour’s Simplicity.

“The 1860 is often referred to as the ‘baby Dufour,’ but in fact it should be the ‘uncle Dufour’ since it was launched before the Simplicity,” Garcia said. He went on to point out that, while the two watches share similar dials, the aesthetics of the 1860 and Simplicity are quite different upon closer inspection – starting with the obvious fact that the Simplicity features a manual-wind caliber.

The dial is stepped and made entirely of gold, also featuring polished gold hands and indices. The result is pure elegance, the epitome of a dress watch, and perhaps the only dial that could be fitting of the caliber 1.96 on display when the watch is turned over. The date window is cut out under the subsidiary seconds at 6 o’clock, keeping the 1860’s appearance clean and symmetrical.

The 36.5mm precious metal case features a thin, slightly stepped bezel, allowing the dial to shine through. Owing to the slimness of the 1.96, the L.U.C. 1860 is a thin, easy-wearing dress watch.

Collecting the L.U.C. 1860

Chopard produced the First Series of the L.U.C. 1860 with the caliber 1.96 from about 1997 through 2002. This First Series features three different references; each was to be produced in four precious metals – yellow gold, pink gold, white gold, and platinum:

Reference 16/1860/2, featuring a sapphire caseback, produced in 1,860 examples of each metal

References 16/1860/1 and 16/1860/4, featuring an officer’s caseback, produced in 100 examples of each metal

Each reference featured four dial variations: silver, black, blue, and salmon. Dial variants weren’t explicitly matched to particular case metals, but attention would’ve certainly been given to aesthetics – for example, only pairing a blue or salmon dial with a white metal. On the sapphire caseback 1860/2, the limited edition number is noted on the outer bezel of the caseback. On the officer’s caseback, it can be found on the inside of the hinged caseback.

But here’s something people don’t know about the L.U.C. 1860: While Chopard intended to produce the numbers noted above, it never actually finished any of these runs. So, there are substantially fewer examples in existence than once believed.

Chopard produced the most examples of the reference 16/1860/2 in yellow gold and rose gold – estimates put production at 500-600 units in each metal. White gold production is estimated at 400 units, while platinum is estimated at 300 units. Meanwhile, it’s estimated that Chopard produced about 50 units in each metal of the 1860/1 (of the intended 100), and 25 examples each of the 1860/4.

It’s also possible to distinguish between earlier and later-produced 1.96 movements. In the early years, the 22kt gold rotors were engraved with a cursive “Chopard.” Later examples (still the Geneva Seal caliber 1.96, to be sure) feature block text “L.U.C.” Additionally, Chopard used only gold rotors in the early years, so an early platinum model might feature a white gold rotor.

Because of the degree of hand-finishing required of each 1.96, production of the caliber was extremely limited in its early years, with total output likely not close to comparing with the likes of Patek Philippe, Jaeger LeCoultre, or Lange. As a point of comparison, KFS said in 2021 Chopard produced 4,000 movements for its entire L.U.C. line. Remember that over the last twenty-five years, Chopard Manufacture has scaled up from a handful of employees to a few hundred.

In addition to the “standard” 1860, a few one-off or custom dials have been found. The most beautiful custom order I’ve seen features a black guilloche dial with baguette indices.

Separately, a rare no-date dial has also been seen. As the story goes, Chopard created this prototype dial with the intent to fit them into a model that would feature a no-date version of the caliber 1.96 – a caliber that was never produced. Still, some of these dials have made their way into collectors’ hands, who have happily placed them into their standard 1860 models, phantom date and all.

Reception of the Caliber 1.96 and L.U.C. 1860

After its release, the caliber 1.96 and L.U.C. 1860 received accolades from all corners of the watch world. As mentioned, writer Walt Odets dubbed the caliber 1.96 the best automatic movement being produced in Switzerland at the time (he also famously decried the Rolex Explorer 14270 around the same time as having “no horological interest whatsoever”), and he was far from alone. Timezone and Swiss magazine Montres Passion/Uhrenwelt named the 1860 their “Watch of the Year” in 1997.

In 2016, Hodinkee’s Louis Westphalen handled a caliber 1.96, writing, “[my] biggest takeaway was to question the frontier between modern and vintage watches, as the 1990s are a grey area and some gems deserve to be re-discovered. It also showed me that many of the things I love with vintage watches can be found in any time period. This Chopard was an impressive first watch that changed the destiny of Chopard, in the same way the reference 96 did for Patek Philippe in the early 1930s.”

As appreciation for the caliber 1.96 and the First Series 1860 would continue to grow, Louis’ words turned out to be prescient.

Life after the caliber 1.96

The Caliber 1.98

Soon after the caliber 1.96 came the Chopard caliber 1.98.

“If we want to talk about the caliber 1.96, we have to talk about the 1.98 and the first Quattro too,” Garcia said. “The Quattro is the logical evolution of the 1.96. The 1.98 is a manual-wind caliber with 4 barrels, featuring a single wire around the barrels that is 1.88m long.” The result is a 9-day power reserve. Like the 1.96, the caliber 1.98 was produced in four variations, and would also carry the Geneva Seal and COSC certification.

The 1.98 marked the beginning of realizing KFS’ vision of producing a caliber that could be modified to produce other calibers and complications. Soon after, Chopard would introduce the L.U.C. 1.02 tourbillon, the L.U.C. CF chronograph, and the L.U.C. 3.97, an original tonneau-shaped caliber.

The Caliber 3.96

In the early 2000s, Chopard transitioned from using the caliber 1.96 in its L.U.C. 1860 to the caliber 3.96. The 3.96 movement uses the same base as the 1.96, but lacks some of the features and finishing that allowed the 1.96 to meet the strict Geneva Seal requirements. On a technical level, the 3.96 does not feature a Breguet overcoil hairspring or swan neck regulator, instead opting for the more common flat hairspring and regulator mechanisms. While both movements are finished to a high degree, the 1.96 features additional hand-finishing, polishing and anglage that the 3.96 does not. However, like the 1.96, the 3.96 is a highly accurate and reliable COSC-certified caliber. You’ll also notice that this later generation of the L.U.C. 1860 that utilizes the caliber 3.96 does not feature the guilloche dial from Metalem.

To this day Chopard still produces a Geneva Seal version of its L.U.C. 96 caliber series, called the 96.01.

An 1860 featuring the caliber 3.96 – note the lack of a swan neck regulator. Like later-produced 1.96 calibers, also note the ‘L.U.C.’ engraving on the rotor instead of the cursive ‘Chopard.’ Credit: Watchuseek.

Re-Issue: Chopard x Revolution and The Rake

In 2018, Chopard, in collaboration with Revolution and The Rake, re-launched a limited-edition L.U.C. 1860 featuring Chopard’s modern 96.01, the descendent of the original 1.96. The release was realized in perhaps the most beautiful – if not rare – dial-case combination of the original 1860, featuring a white gold case and salmon dial. The ten-piece limited edition quickly sold out, illustrating the continued appreciation collectors have for the L.U.C. 1860 and the caliber 1.96.

[Ed. Note: Since the original publication of this article, Chopard has re-introduced the original L.U.C 1860 in Lucent Steel. Here’s my hands-on review for Hodinkee.]

The Enduring Impact of the Caliber 1.96

The L.U.C. and the caliber 1.96 are emblematic of fine watchmaking in the 1990s: a family-owned, independent house enlisting the help of a master independent watchmaker to spare no expense in developing a new micro-rotor movement that competed with the world’s best. The investment in horology came at a make-or-break moment for Chopard and its watchmaking department, and it succeeded.

“I always like to talk about Lange, because our journey is similar,” Director of Patrimony Garcia said. “Lange re-launched in 1994 with its first wristwatches. We re-started in 1996 with our first caliber, and then introduced our first 1860.” Two new manufactures that both set the watch space on fire when they stepped into the newly revitalized world of mechanical watchmaking in the 1990s.

“KFS was very much motivated by Patek and Lange & Sohne,” Garcia continued. “Chopard had a family vision it was trying to re-create. We’re the last family business producing both watches and jewelry, and it’s a great honor to still be independent.”

This continued independence is no doubt thanks in part to the bold decision to revive Chopard as a proud manufacture, and one capable of producing one of the best automatic movements ever, the Chopard caliber 1.96.

—

Thank you to the collectors who assisted with this article, most notably Juan Garcia, the Director of Patrimony at Chopard. Thanks also to Louis Westphalen (now of Daniel Roth) for turning me onto the Chopard caliber 1.96 with that 2016 Hodinkee article and sharing his resources.

Really bullish on chopard going forward.

Thanks for bringing it back, I've been missing this one.