Cartier Crash and Geneva Auction Week Recap

Rewriting Seiko's history by discovering its first mountaineering watch

Rescapement is a weekly newsletter about watches. Smash the subscribe button to get it delivered to your inbox every week:

A London Cartier Crash sold for a record $853k last week so I wrote about it.

I’ve wanted to do a more comprehensive article about the Cartier Crash for a while. But I didn’t want it to be about all the noise surrounding the Crash. Not the big auction results; not John Goldberger taking a photo of Tyler the Creator wearing one, or Kanye tweeting a photo of one.

Sure, those things were all the impetus for writing about the Crash. Last week, Sotheby’s sold an original London Crash for $853k. It’s one of the biggest vintage Cartier results ever. But that’s not why I wanted to write about the Crash.

It’s funny, much the way the actual origin story of the Crash has been subsumed by the myth of the Crash (that designers were inspired to create the Crash by a molten Cartier Baignoire Allongée involved in a car crash), today the Crash has been similarly overshadowed by a certain myth-making.

Over on H*dinkee, I tried to tell what I feel like is the more interesting story about the Cartier Crash, the real story.

To do that, we have to head back to 1960s London, aka Swinging Sixties. Mods, miniskirts, Mick Jagger — all roamed the streets of London, shocking the city out of its post-war malaise and into the epicenter of style. “As opposed to the 1950s, which had been clouded in post-war austerity and restraint, the 1960s was a decade of rebellion with the young challenging the status quo and wanting to be different from their parents,” Francesca Cartier Brickell, author of the excellent book The Cartiers: The Untold Story of the Family Behind the Jewelry Empire (and granddaughter of Jean-Jacques Cartier), told me.

The intersection of history and design is endlessly fascinating to me. The last three freelance articles I’ve written have indirectly explored this intersection:

1950s: The Junghans Max Bill, the minimalist product of the Bauhaus-influenced designer. Just put the Max Bill (a product of those austere 50s), next to the Crash and you can begin to understand the revolution of the Swinging Sixties that Cartier Brickell mentions

1960s: The maximalist Cartier Crash

1990s: Marc Newson’s Ikepod explored bold, natural shapes, coming off of the excess of the 80s, just as the dot-com bubble rapidly inflated

We always say that trends come and go, and it’s true, but it’s interesting to reflect on why that’s the case. Why was the Crash created in the Swinging Sixties in London? Why has it had a certain rebirth over the past couple of years? What’s similar about our current time and the 1960s in London?

💩 Read the full article on H*dinkee here.

p.s. don’t go to the H*dinkee comments for any insightful convos about hip-hop.

Significant Lots

Episode 2 of Significant Lots, the joint podcast project between Eric Wind, Gabriel Benador, Charlie Dunne, and myself, is here! We discuss WTF might’ve happened with that tropical Omega Speedmaster that Phillips sold for $3.4m, buckoo bucks for Journe boxes, and everything else from the weekend that was in Geneva.

Additional Show Notes:

Omega Speedmaster CK2915-1, sold by Sotheby's for CHF 327,600

Roger Smith Series 2, sold for CHF 655,000 at Phillips

Christian Klings, sold for CHF 252,000 at Phillips

Rolex MilSub, sold for CHF 504,000 at Phillips

Books on Time

Re-discovering Seiko’s history with its first mountaineering watch

By: Charlie Dunne

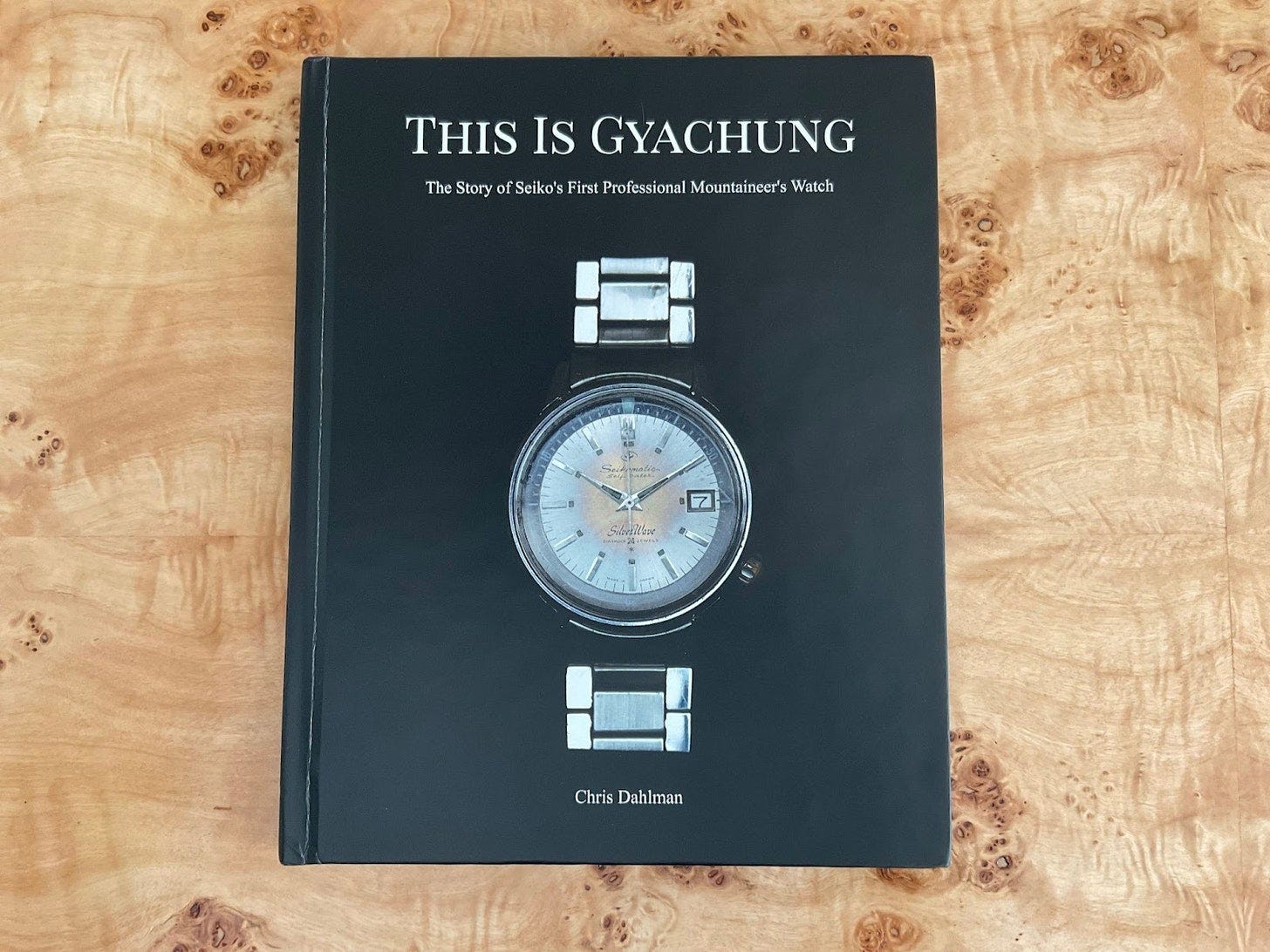

Chris Dahlman's debut publication This Is Gyachung explores the fascinating story of the 1964 Japanese Himalayan Expedition to Gyachung Kang mountain.

Upon acquiring a Seiko Silverwave in 2018, Dahman noticed a mysterious case back engraving that would serve as the impetus to discovering Seiko's first mountaineering and purpose-built expedition watch, and ultimately, rewriting the brand's history.

While this appears to be a watch book on the surface, it is much more. There are certainly specs for the watch geeks, but you will quickly get drawn into the stories of the individuals who went on this Japanese Expedition. As was the author’s intention, the watch doesn’t necessarily need to be the focal point. Although it most certainly plays a role after the reader is introduced to it.

“This book is my answer to the question ‘Why do I collect?’ It’s an object, but it can be so much more. It’s about people and experiences.”

📚 Read Charlie’s full review of the book This is Gyachung.